The direct answer to “is Inconel magnetic?” is nuanced. It’s also critical for material selection. Inconel is generally non-magnetic. However, certain grades and specific material conditions can cause it to show very weak magnetic properties. This phenomenon is known as paramagnetism.

This distinction isn’t just academic theory. For engineers, technicians, and procurement specialists working on critical applications, understanding these subtle differences prevents costly errors. It also prevents equipment failure and safety hazards.

This guide provides a detailed, practical examination of Inconel’s magnetic properties. We will explore the material science behind these properties. We’ll also look at the exceptions to the non-magnetic rule. Finally, we’ll show how to properly specify and verify Inconel for your most demanding projects.

Table of Contents

The Science of Inconel Magnetism

To understand Inconel’s magnetic behavior, we must first look at its fundamental atomic structure. We also need to examine its chemical composition. The alloy’s properties are not accidental. They are a direct result of deliberate metallurgical design.

Austenitic Crystal Structure

The primary reason for Inconel’s non-magnetic nature is its austenitic crystal structure. This is also known as a face-centered cubic (FCC) lattice.

In this atomic arrangement, atoms sit at each corner of a cube. They also sit in the center of each face. This specific, symmetrical configuration does not allow for the spontaneous alignment of electron spins. This alignment is the root cause of ferromagnetism (the strong magnetism seen in iron).

Therefore, any material that maintains a stable austenitic structure will be inherently non-magnetic in its base state. This includes Inconel.

Nickel’s Stabilizing Influence

Inconel is a family of nickel-chromium-based superalloys. Nickel content often exceeds 50%. This high concentration of nickel is the key stabilizing agent for the austenitic structure.

Nickel ensures the face-centered cubic lattice remains stable from cryogenic temperatures up to its melting point. This makes Inconel far more magnetically stable than some other common alloys.

For instance, austenitic stainless steels like 304 or 316 also have an FCC structure. But they have much lower nickel content. This makes their austenite less stable. It allows transformation into magnetic martensite when subjected to cold working. Inconel’s high nickel content largely prevents this transformation. It preserves the non-magnetic character even after forming or machining.

Understanding Magnetic Permeability

The most precise way to quantify a material’s magnetic response is through its relative magnetic permeability (μr). This value measures how much a material can concentrate magnetic lines of flux compared to a perfect vacuum.

A perfect vacuum has a permeability of exactly 1.0. Materials with a permeability slightly above 1.0 are paramagnetic. This means they are very weakly attracted to a magnetic field. Materials with a permeability much greater than 1.0 are ferromagnetic.

For most Inconel alloys in their soft, annealed condition, the magnetic permeability is extremely low. It typically ranges from 1.001 to 1.01. This value confirms they are essentially non-magnetic for almost all practical purposes. This near-vacuum permeability stands in stark contrast to the materials used in high-strength magnets. For example, those found in Neodymium Magnets are designed to concentrate magnetic flux lines.

Exceptions to Non-Magnetic Behavior

While the baseline for Inconel is non-magnetic, the answer to “is Inconel 718 magnetic?” can be different from the answer for Inconel 625. Certain factors can introduce weak magnetism. Understanding these exceptions is vital for material specifiers.

Influence of Alloy Grade

Not all Inconel is created equal. The specific alloying elements and heat treatment response of each grade affect its magnetic properties. Precipitation-hardenable grades are more susceptible to becoming weakly magnetic than solid-solution strengthened grades.

We can see a clear difference when comparing common grades.

Alloy Grade | Typical Magnetic Permeability (Annealed) | Tendency to Become Magnetic After Cold Work/Aging | Key Notes |

Inconel 625 | ~1.001 | Very Low | A solid-solution alloy, remains non-magnetic to cryogenic temperatures. Ideal for many non-magnetic applications. |

Inconel 718 | ~1.001 (Annealed) | Moderate | An age-hardenable alloy. The aging heat treatment precipitates phases (like gamma prime and double prime) that can slightly increase permeability. |

Inconel X-750 | ~1.002 (Annealed) | Moderate to High | Also age-hardenable. The heat treatment used to achieve high strength can significantly increase its magnetic response compared to other Inconel grades. |

Inconel 600 | ~1.01 | Low | A standard solid-solution alloy with good stability, but its properties can be influenced by processing history. |

As the table shows, age-hardenable superalloys like Inconel 718 and X-750 can have phases precipitate during heat treatment that are slightly magnetic. This raises the overall permeability. However, it still does not make the material “magnetic” in the common sense of attracting a paperclip. For detailed specifications on each grade, refer to the official data from manufacturers like Special Metals Corporation.

Effects of Cold Work

Processes like forging, drawing, rolling, and heavy machining introduce stress and dislocations into the material’s crystal lattice. This is known as the effect of cold work on magnetism.

While Inconel’s stable austenitic nickel-chromium alloy structure resists the phase transformations seen in stainless steel, severe cold work can still slightly disrupt the atomic arrangement. This disruption can cause a minor increase in magnetic permeability in some grades.

In our experience working with high-precision components, we’ve observed that a heavily machined Inconel 718 part may register a faint response on a sensitive gaussmeter. Meanwhile, an annealed stock piece of the same material will not. This is a critical consideration for components intended for use near sensitive magnetic sensors.

Impact of Heat and Welding

Heat treatment and welding are other critical factors. For precipitation-hardenable grades like Inconel 718, the aging process is intentional and necessary to develop strength. This process involves heating the material to allow specific strengthening phases to form within the microstructure.

Some of these strengthening phases are crucial for mechanical performance. However, they can possess a slight magnetic character. This is a trade-off between mechanical strength and magnetic purity.

Welding creates a localized heat-affected zone (HAZ) where the material’s microstructure is altered. This zone can have different residual stresses and phases compared to the base metal. This potentially leads to localized variations in magnetic properties.

Temperature and Curie Point

The Curie temperature is the critical point at which a ferromagnetic material loses its magnetic properties and becomes paramagnetic. For the base elements in Inconel, like nickel, the Curie point is 358°C (676°F).

However, in the Inconel alloy, nickel’s ferromagnetic behavior is suppressed by the overall austenitic structure. The concept is more relevant when discussing the minor phases that can precipitate. These phases may have their own Curie temperatures. But their volume is so small that their effect on the bulk material is minimal.

For most engineering purposes, the focus remains on the material’s permeability at its service temperature. This is particularly true for materials for MRI environments or cryogenic applications. For Inconel, this permeability is consistently very low.

Specifying and Verifying Inconel

Simply requesting “Inconel” is not enough to guarantee non-magnetic properties. For critical applications, a precise specification and verification process is essential to avoid costly errors. This is a practical guide for procurement, engineering, and quality control personnel.

Specifying on Purchase Orders

Your purchase order is the first line of defense. It must be unambiguous and detailed.

- Specify the Exact Alloy. Never use a generic term. Instead of “Inconel,” specify “Inconel alloy 625 per AMS 5666” or “Inconel alloy 718 per AMS 5662.”

- Define the Material Condition. This is crucial. For the lowest magnetic permeability, specify the “solution annealed” or “annealed” condition. Avoid ordering material in an “as-rolled” or unknown work-hardened state unless it is intentional.

- State Magnetic Permeability Requirements. For the most sensitive applications, you must specify a maximum acceptable magnetic permeability. Examples include aerospace alloy magnetism or particle physics equipment. A common requirement is “Relative magnetic permeability (μr) shall be less than or equal to 1.01.” Reference a testing standard like ASTM A342.

- Request Material Certifications. Always require a Mill Test Report (MTR) or a Certificate of Conformance with every shipment. This document must show the precise chemical composition and detail the heat treatments performed.

Verification and Testing

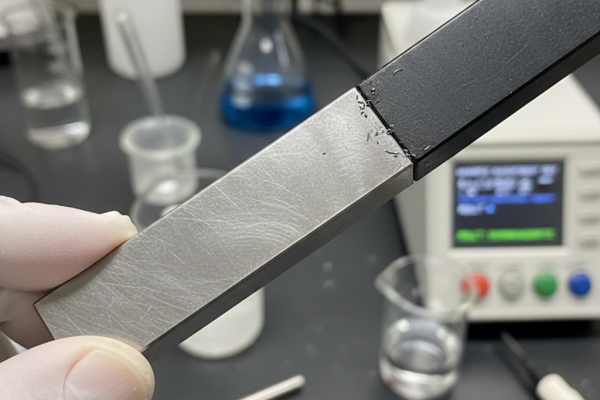

Trust, but verify. A simple magnet test is often useless. It will not detect the weak paramagnetism that can still interfere with sensitive equipment.

Method 1: Using a Calibrated Gaussmeter. A sensitive, calibrated gaussmeter or magnetometer is the professional standard for verification. This instrument measures the actual magnetic field of a material sample. It provides a quantitative value. For precise quantitative analysis, a calibrated gaussmeter is the professional standard. These magnetic measurement tools can detect the very subtle paramagnetic response that a simple magnet would miss.

Method 2: Conforming to Industry Standards. When a specific permeability value is required by contract, testing must be performed according to established standards. This ensures the results are accurate and repeatable. Adherence to standards like ASTM A342 (“Standard Test Methods for Permeability of Feebly Magnetic Materials”) ensures a repeatable and verifiable testing process.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

We have seen several common mistakes lead to project delays and failures.

Pitfall 1: Assuming all “Inconel” is the same.

Solution: Always specify the exact grade and condition. The magnetic properties of Inconel X-750 are vastly different from those of Inconel 625.

Pitfall 2: Contamination during machining or handling.

Solution: Use dedicated tooling and clean work areas when machining non-magnetic alloys. Contact with carbon steel dust, grinding media, or tooling can “smear” ferromagnetic particles onto the surface of the Inconel part. This makes it appear magnetic.

Pitfall 3: Ignoring the effects of post-weld heat treatment.

Solution: If the final application is magnetically sensitive, test the final, welded, and heat-treated assembly. Do not rely solely on the MTR of the raw material. Subsequent processing can alter the properties. For more about magnetic permeability, you can read resources like Engineering Toolbox.

Comparing Alloys

To make an informed decision, it’s helpful to see how Inconel’s magnetic properties stack up against other common engineering materials. This context helps clarify when Inconel is the right choice. It also shows when another non-magnetic superalloy or material might be more suitable.

Inconel vs. Stainless Steel

This is one of the most common comparisons. While both can be non-magnetic, there is a critical difference in stability.

Austenitic stainless steels like 316L are non-magnetic in the annealed state. However, their less stable austenite can easily transform into magnetic martensite when cold-worked. A bent 316L tube may become magnetic at the bend.

Inconel alloys, with their high nickel content, offer far superior magnetic stability. They resist this work-induced transformation. This makes them a more reliable choice for applications that involve forming, machining, or might experience stress in service. Other stainless steel families, like duplex and martensitic (e.g., 410, 17-4 PH), are always ferromagnetic.

Versus Other Non-Magnetic Alloys

Inconel is not the only option for non-magnetic applications. The choice often depends on a combination of properties. These include strength, corrosion resistance, and cost.

Monel 400, a nickel-copper alloy, is also non-magnetic and offers excellent corrosion resistance, particularly in marine environments.

Titanium and its alloys (like Ti-6Al-4V) are completely non-magnetic. They have the added benefit of a much lower density than Inconel. This makes them ideal for lightweight aerospace components where magnetism is a concern.

Copper alloys, such as beryllium copper and aluminum bronze, are also non-magnetic and offer high thermal and electrical conductivity.

Alloy Magnetic Property Table

This table provides a high-level overview for quick comparison.

Alloy | General Magnetic Behavior | Typical Magnetic Permeability (μr) | Use Case Notes |

Inconel 625 (Annealed) | Non-Magnetic (Paramagnetic) | ~1.001 | Ideal for cryogenic, high-strength, non-magnetic use. Very stable. |

Inconel 718 (Aged) | Weakly Magnetic (Paramagnetic) | 1.001 – 1.01 | Use with caution in highly sensitive areas. Strength is primary; low magnetism is secondary. |

Stainless Steel 316L (Annealed) | Non-Magnetic (Paramagnetic) | ~1.005 | Excellent general-purpose non-magnetic alloy. |

Stainless Steel 304 (Cold-Worked) | Weakly to Moderately Magnetic | 1.1 – 10+ | Becomes magnetic after forming, welding, or machining. Unreliable for non-magnetic needs. |

Carbon Steel (1018) | Ferromagnetic | >1000 | Structural material. Always strongly magnetic. |

Titanium (Ti-6Al-4V) | Non-Magnetic (Paramagnetic) | ~1.00005 | Excellent strength-to-weight ratio. Completely non-magnetic for all practical purposes. |

Monel 400 | Non-Magnetic (Paramagnetic) | ~1.001 | Superior marine corrosion resistance. Stays non-magnetic. |

A deep dive into alloy microstructures can be found on resources like the University of Cambridge’s DoITPoMS library.

Critical Non-Magnetic Applications

The demand for high-strength, non-magnetic materials is driven by some of the most advanced technological fields. In these sectors, Inconel’s unique combination of properties makes it an indispensable material.

- Medical Equipment (MRI Machines). Components located within or near the powerful magnetic field of an MRI scanner must be non-magnetic. Any ferromagnetic material would distort the diagnostic image. It would also create dangerous projectile risks and interfere with the machine’s operation. The need for non-magnetic materials is paramount in advanced medical imaging. This is a field where magnets play a critical role in diagnostics and treatment.

- Aerospace and Avionics. Inconel is used for components near sensitive electronic systems. These include navigation equipment and flight sensors. Using a non-magnetic material prevents magnetic interference (EMI) that could compromise the accuracy and reliability of these critical systems. This is a key topic in aerospace alloy magnetism.

- Particle Accelerators and Physics Research. Laboratories like CERN use powerful magnetic fields to steer particle beams. The structures and instrumentation within these accelerators must be completely non-interactive with these fields. Inconel’s low permeability and high strength make it suitable for vacuum chambers and support structures in these extreme environments.

- Oil & Gas Downhole Tooling. In Measurement While Drilling (MWD) and Logging While Drilling (LWD) operations, sensitive magnetometers are used to survey the direction of the wellbore. These instruments are housed in non-magnetic drill collars, often made of specialty alloys. This isolates them from the magnetic interference of the steel drill string. Inconel is sometimes used in components for these tools due to its strength and corrosion resistance.

- Cryogenic Applications. Inconel alloys like 625 and 718 not only remain non-magnetic at cryogenic temperatures but also retain excellent ductility and strength. This makes them essential for handling liquefied natural gas (LNG). They’re also vital for constructing components for superconducting magnets. This is documented in resources like this NASA technical paper on Inconel 718 for rocket engine applications.

Conclusion: The Right Choice

We return to our initial question: is Inconel magnetic? The answer is fundamentally no, but with critical exceptions. This family of high-nickel, austenitic superalloys is designed to be non-magnetic. This property is rooted in its stable face-centered cubic crystal structure.

The complexity arises with specific grades, processing, and heat treatments. The age-hardening required to give Inconel 718 its renowned strength can also introduce a slight magnetic response. Likewise, heavy cold working can minutely increase the magnetic permeability of an otherwise non-magnetic alloy.

Ultimately, ensuring performance and safety comes down to diligence. Engineers and procurement professionals must move beyond a simple yes/no question. They need to focus on precise specification and verification. By defining the exact alloy, condition, and maximum allowable magnetic permeability, and by testing the final product, you can harness Inconel’s superior properties with confidence. This applies even in the most magnetically sensitive applications.

We are a manufacturer specializing in the research and development of magnets with years of industry experience. Our product offerings include NdFeB magnets, ferrite magnets, and custom magnetic components. Our goal is to provide high-quality magnetic solutions to customers worldwide, and we also offer OEM/ODM customization services. If you have any questions about magnets or custom applications, please feel free to contact our team of experts.

Facebook

Twitter

LinkedIn

X