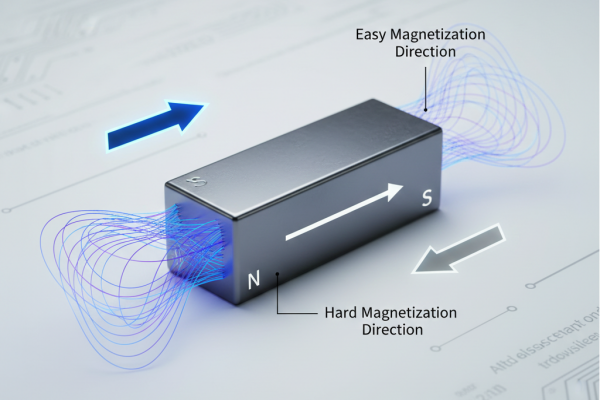

Magnet anisotropy means magnetic properties change based on direction. Simply put, a magnet works best when magnetized along one specific path called the “easy axis.” It’s weaker along other directions, known as “hard axes.”

This isn’t just a minor detail. It’s the main reason modern rare-earth magnets like Neodymium (NdFeB) and Samarium Cobalt (SmCo) pack such incredible power. Understanding what is magnet anisotropy and why it is important for magnet selection matters for engineers, designers, and buyers working with high-performance magnetic systems.

This property controls a magnet’s ultimate strength. It determines resistance to demagnetization. It affects how magnets must be handled during manufacturing and assembly. Get it wrong, and you’ll face poor performance, part failures, and expensive delays.

This guide offers a complete, practical look at magnet anisotropy. We’ll cover:

- A clear explanation of magnet anisotropy and its opposite, isotropy.

- How it gives high-performance magnets their strength and stability (coercivity).

- Its vital role in applications like efficient motors and precision sensors.

- A practical system for choosing the right magnet based on anisotropy properties.

Table of Contents

Core Concept: Anisotropy vs. Isotropy

To understand why anisotropy matters, you need to know how it differs from isotropy. This difference is the first critical step in magnet selection. It sets the performance limit of your chosen material.

The Wood Grain Analogy

Think of a wood block. Splitting along the grain is much easier than chopping across it. The direction along the grain is the “easy axis” for splitting. The direction across the grain is the “hard axis.”

Anisotropic magnets work the same way. They’re built with a preferred internal structure—a “magnetic grain.” This structure makes it easy to magnetize them to very high levels in one specific direction.

On the flip side, magnetizing them along a “hard axis” takes enormous energy. This same principle makes them highly resistant to demagnetization, especially from forces not aligned with their easy axis.

At a Glance: A Comparison

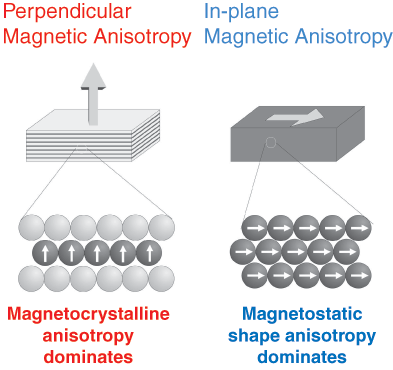

Isotropic magnets are the opposite. They have no internal “grain” or preferred direction. Their magnetic domains point randomly. This creates uniform magnetic properties in all directions.

This makes them more flexible in one way—they can be magnetized in any direction after manufacturing. But this lack of internal alignment costs them magnetic strength. Anisotropic magnets, with their aligned structure, are far more powerful in their intended direction.

The choice between them is a primary design decision. It’s based on performance needs versus manufacturing flexibility.

Feature | Isotropic Magnets | Anisotropic Magnets |

Internal Structure | Randomly oriented magnetic domains | Aligned crystalline structure |

Magnetization | Can be magnetized in any direction after production | Must be magnetized along the pre-defined “easy axis” |

Magnetic Strength | Lower | Significantly Higher |

Typical Materials | Bonded NdFeB, some Ferrites, cast Alnico | Sintered NdFeB, SmCo, some Ferrites, certain Alnico grades |

Common Use Case | Applications needing a complex magnetic field pattern; low-cost sensors; refrigerator magnets | High-performance motors, generators, high-end speakers, MRI, precision sensors |

Anisotropy Creates Superior Magnets

Procurement managers and engineers often ask: “Why are sintered NdFeB magnets so much stronger than other types?” The answer lies almost entirely in magnetocrystalline anisotropy.

The Power of the Crystal

High-performance rare-earth materials like Neodymium-Iron-Boron (NdFeB) and Samarium-Cobalt (SmCo) get their immense power from their specific atomic crystal structure.

In NdFeB, atoms form a tetragonal crystal lattice (Nd2Fe14B). This unique physical structure creates an extremely strong built-in “preference.” The magnetic moments of atoms want to align along a single crystallographic axis—the c-axis. This inherent directional preference at the atomic level is magnetocrystalline anisotropy.

During sintered magnet manufacturing, this property gets harnessed. The raw alloy is ground into fine, single-crystal powder. This powder goes into a die and faces a powerful external magnetic field. The field physically rotates each microscopic particle so its “easy axis” aligns with the applied field.

The powder is then pressed and sintered (heated below its melting point) to fuse the aligned particles into a solid block. This process permanently locks in the powerful, unified directional preference. It creates a monolithic magnet where trillions of individual crystals all point the same way. This is why a product like a Neodymium Magnet can store such massive magnetic energy.

Anisotropy and Coercivity

This leads to one of the most critical parameters on any magnet datasheet: Coercivity (Hci). Coercivity measures a material’s resistance to demagnetization by opposing external magnetic fields or elevated temperatures.

The link is direct and powerful: high magnetocrystalline anisotropy creates high coercivity.

Because all magnetic moments are “locked” into the easy axis, it takes tremendous external energy to force them to rotate away from that preferred direction. This resistance to change is what we measure as coercivity. It’s the secret behind the “permanence” of permanent magnets.

The practical difference is staggering. A typical high-grade Sintered NdFeB magnet can have intrinsic coercivity (Hci) exceeding 20,000 Oersteds (Oe). Some grades push past 30,000 Oe. In contrast, a standard isotropic Ferrite (ceramic) magnet might have coercivity around 3,000-4,000 Oe. This massive performance gap comes almost entirely from NdFeB’s superior magnetocrystalline anisotropy.

For more on coercivity physics, a resource like the Encyclopedia Britannica’s entry on magnetic hysteresis provides excellent background.

Practical Applications

Theory matters, but the real value of understanding magnet anisotropy shows up in how it enables modern technology. For engineers and product designers, leveraging anisotropy isn’t optional. It’s required for competitive performance.

Case Study 1: Electric Motors

Modern electric motor design (for EVs, drones, industrial servos, and robotics) aims to maximize torque and efficiency while minimizing size, weight, and waste heat.

Anisotropy is key to achieving this power density. In high-performance brushless DC (BLDC) motors, precisely shaped anisotropic magnets like sintered NdFeB arc segments are arranged in the rotor. Their “easy axis” points radially or in a Halbach array.

This focuses powerful, concentrated magnetic flux directly across the air gap. There it interacts with electromagnetic fields of the stator coils. This precise, powerful interaction generates maximum torque with minimal electrical loss.

From our experience, engineering clients in EV and drone industries know that using isotropic magnets would be unthinkable. The resulting motor would be drastically larger, heavier, and less efficient. It would overheat quickly under load. Proper orientation of anisotropic segments during assembly is a non-negotiable, critical-to-quality step for achieving performance targets. For in-depth motor design principles, publications from the IEEE Xplore Digital Library are authoritative resources.

Case Study 2: Precision Sensors

In applications like linear encoders, rotary position sensors, and automotive safety systems, the goal is reliable, repeatable, and precise detection of position or movement.

Anisotropic magnets are essential for creating sharp, well-defined magnetic field gradients. When a Hall effect sensor or magnetoresistive sensor passes through this distinct field, it produces a clean, unambiguous electrical signal with sharp transition. This allows precise triggering and measurement.

If an isotropic magnet were used, its weaker and more diffuse magnetic field would create a “mushy” signal. This leads to positional uncertainty, signal jitter, and unreliable performance. That’s unacceptable in safety-critical or high-precision systems. An axially magnetized anisotropic disc magnet produces a clean, predictable field ideal for such applications.

Case Study 3: High-Fidelity Audio

The core of a high-end speaker or headphone is its “motor assembly.” This consists of a voice coil moving within a strong, static magnetic field. The goal is powerful and perfectly accurate sound reproduction.

To do this, the motor requires very strong and highly uniform magnetic field concentrated in a small air gap. Anisotropic magnets, such as precisely machined NdFeB or Ferrite rings, create this field.

Higher strength and uniformity enabled by anisotropy allow greater Lorentz force on the voice coil for a given input current. This provides tighter control over diaphragm movement. The result is lower distortion, better transient response, and more faithful reproduction of the original audio signal. Many audio applications require very specific geometries. This makes Custom Magnet solutions necessary to optimize the magnetic circuit.

A Practical Selection Guide

Understanding theory is the first step. Next is applying it to make informed purchasing and design decisions. This guide helps engineers and procurement professionals decode datasheets and select optimal materials.

Decoding the Datasheet

When you review a magnet’s technical data, several key parameters tie directly to its anisotropic nature.

- Maximum Energy Product (BH)max: Often considered the primary “figure of merit” for magnet strength, measured in MegaGauss-Oersteds (MGOe). It represents maximum energy that can be stored in the magnet. This value is directly enabled by high anisotropy, which allows both high residual magnetism and high resistance to demagnetization.

- Intrinsic Coercivity (Hcj): This is the truest measure of a material’s inherent resistance to demagnetization from external fields and temperature. It’s the most direct indicator of the strength of the material’s magnetocrystalline anisotropy. For high-temperature applications, choosing a grade with high Hcj is paramount.

- Remanence (Br): This is magnetic flux density remaining in the material after the external magnetizing field is removed. In a well-designed anisotropic magnet, where crystals are highly aligned, remanence will be very close to the material’s saturation magnetization.

Anisotropic Magnet Comparison

Choosing the right anisotropic material involves trade-offs between performance, temperature resistance, and cost. This table provides a high-level comparison for industrial applications.

Magnet Type | Key Anisotropic Benefit | Typical (BH)max (MGOe) | Intrinsic Coercivity (Hcj) | Max Temp. | Best For… |

Sintered NdFeB | Highest strength per volume | 35 – 55 | High to Very High | 80°C – 230°C | Motors, generators, separators, where max power/min size is key. |

Sintered SmCo | Excellent high-temp stability | 18 – 32 | Very High | 250°C – 350°C | Aerospace, military, high-temp motors and sensors, medical devices. |

Hard Ferrite | Lowest cost for performance | 3.8 – 5.0 | Moderate | ~250°C | General purpose motors, speakers, holding applications, toys. |

Alnico | Best thermal stability (low tempco) | 5 – 9 | Low | ~500°C | High-temp sensors, guitar pickups, scientific instruments. |

For standardized definitions of these grades, it’s helpful to refer to organizations like the Magnetic Materials Producers Association (MMPA).

Specifying Magnetization Direction

A critical communication step in procurement is specifying magnetization direction. Simply ordering an “anisotropic magnet” isn’t enough. You must define the intended “easy axis” relative to the magnet’s physical geometry.

A common mistake we see is customers ordering rectangular blocks without specifying which face should be the north pole. This ambiguity can lead to production delays or, worse, receiving a part that’s unusable in their assembly. Always provide a clear drawing with the magnetization axis marked.

Common directions include:

- Axially Magnetized: A disc or cylinder magnetized through its thickness. This is the most common direction for round magnets.

- Diametrically Magnetized: A disc or cylinder magnetized across its diameter, with poles on the curved sides.

- Radially Magnetized: A ring magnet where poles are on the inside and outside diameters. This requires special manufacturing and is often used in advanced motors and couplings.

- Through-Width/Through-Length: For block magnets, specifying which dimension the magnetic axis follows.

Clear understanding of all available Magnet Materials and their manufacturing constraints is vital for successful design.

The Science Behind

For researchers and senior engineers, a deeper look into how anisotropy is created and measured can reinforce the importance of quality control and material science in magnet production.

Manufacturing Process

Creating a high-performance anisotropic magnet is a sophisticated metallurgical process. For sintered rare-earth magnets, the steps are:

- An alloy of constituent elements (e.g., Neodymium, Iron, Boron) is created in a vacuum induction furnace.

- The resulting ingot is crushed and then jet-milled into fine powder, where each particle is a tiny single crystal.

- This powder is placed into a die cavity within a large press. A powerful external magnetic field, often pulsed, is applied. This field provides torque to physically rotate every microscopic particle so its crystallographic “easy axis” aligns with the field.

- While the alignment field is active, the powder is compacted under immense pressure into a “green” block.

- This block is then sintered in a vacuum furnace at high temperature (e.g., over 1000°C for NdFeB). This fuses particles together, permanently locking in their collective alignment and creating a solid, dense, and powerfully anisotropic magnet. The sintering process is a core competency in materials science, as explained in resources from journals like Nature Materials.

Professional Measurement

Verifying properties of an anisotropic magnet requires specialized equipment. This QC step is essential to guarantee that a magnet meets its specified grade.

- Vibrating Sample Magnetometer (VSM): This is the gold standard for plotting the B-H curve (or hysteresis loop) of a magnetic material sample. From this curve, key parameters like Remanence (Br), Coercivity (Hc), and Maximum Energy Product (BH)max are precisely calculated.

- Torque Magnetometer: This instrument directly measures material anisotropy. It works by placing a sample in a rotating magnetic field and measuring torque required to turn it away from its easy axis. This provides direct measurement of anisotropy energy, confirming the quality of the material’s crystal alignment.

Instrument manufacturers like Lake Shore Cryotronics provide detailed information on the principles behind these advanced measurement systems.

Conclusion: Harnessing Directional Power

The concept of magnet anisotropy isn’t merely an academic detail. It’s the cornerstone of modern permanent magnet technology. It’s the guiding principle that allows us to engineer materials with extraordinary power and stability.

Key Takeaways

- It’s Directional: Magnet anisotropy is a magnet’s inherent directional preference, creating an “easy axis” where it’s strongest and most stable.

- It’s the Source of Power: Magnetocrystalline anisotropy is the fundamental property that gives rare-earth magnets their immense strength and high coercivity.

- It’s Application-Critical: High-performance motors, precision sensors, and high-fidelity audio systems are impossible to build without leveraging the focused power of anisotropic magnets.

- It’s Key to Selection: Understanding what is magnet anisotropy and why it is important for magnet selection is essential for interpreting datasheets and choosing the right material for your project’s cost, performance, and environmental needs.

Put This Knowledge into Action

With a firm grasp of magnet anisotropy, you’re now better equipped to specify, source, and implement the perfect magnet for your application. You can communicate requirements with greater precision. You can make more informed decisions that balance cost and performance.

If you’re designing a high-performance system or need to source magnets with specific and reliable directional properties, our team of experts is here to help. Explore our range of high-performance Neodymium Magnets and our capabilities in creating Custom Magnet Solutions to find the right fit for your project.

We are a manufacturer specializing in the research and development of magnets with years of industry experience. Our product offerings include NdFeB magnets, ferrite magnets, and custom magnetic components. Our goal is to provide high-quality magnetic solutions to customers worldwide, and we also offer OEM/ODM customization services. If you have any questions about magnets or custom applications, please feel free to contact our team of experts.

Facebook

Twitter

LinkedIn

X