What are magnetic poles? Simply put, they are specific points on a magnet where its magnetic force is strongest.

Every magnet has at least two poles: a North pole (N) and a South pole (S). Think of these poles as gateways. The magnet’s invisible force projects out and returns through them.

They control how magnets interact with each other and with other magnetic materials. The basic law of magnetism is simple and unchanging: opposite poles attract (North attracts South), and like poles repel (North repels North, and South repels South).

Understanding this core principle is the first step toward mastering magnetism.

Key Takeaways:

- Poles are the points of maximum magnetic strength on a magnet.

- Every magnet is a dipole, meaning it has both a North pole and a South pole.

- The universal law of magnetism is that opposites attract and likes repel.

- You can never isolate a single pole; if you cut a magnet, you create two smaller magnets, each with its own North and South pole.

Table of Contents

The Science of Magnetism

To truly understand magnetic poles, we must look beyond the simple definition. We need to explore the underlying physics. This is where the abstract concept of a pole becomes a real force.

We will explore the rules that define them. We’ll visualize the fields they create. And we’ll understand why they are inseparable.

Defining North and South

How do we know which pole is North and which is South? The naming system is based on our planet.

If a bar magnet hangs freely and can rotate without friction, one end will always point toward Earth’s geographic North Pole.

By universal agreement, this pole—the one that seeks geographic North—is called the magnet’s North pole.

The opposite end is the magnet’s South pole. This simple relationship is how all compasses work.

Visualizing the Invisible

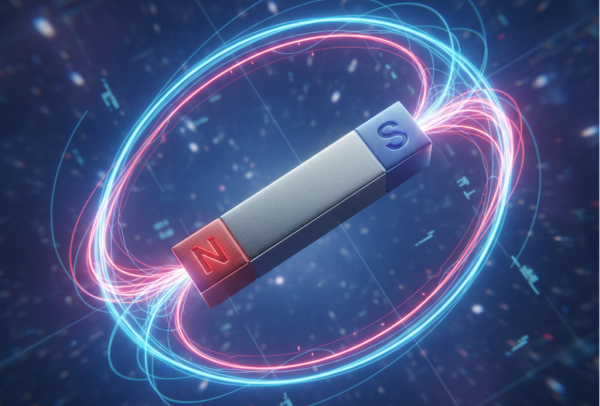

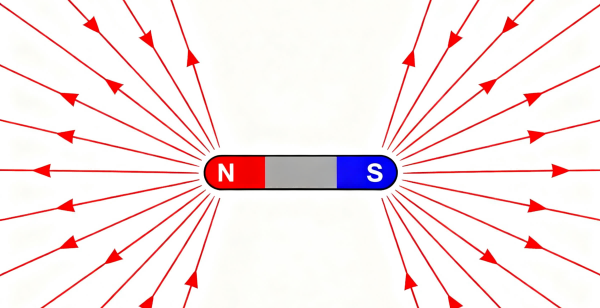

A magnet’s influence is described by its magnetic field. This is an invisible area of force surrounding it. To help us see this, we use magnetic field lines.

These are imaginary lines that map the direction and strength of the magnetic force. They have several key properties.

First, magnetic field lines always form closed loops. They never start or end at a single point.

Second, they never cross one another. The path of the force is unique at every point in space.

Third, the density of the lines shows the strength of the field. Where the lines are closest together—at the poles—the magnetic force is strongest.

By agreement, we say that magnetic field lines flow from the North pole to the South pole on the outside of the magnet.

Inside the magnet, these lines continue the loop. They flow from the South pole back to the North pole, making a complete, unbroken circuit.

Attraction and Repulsion

The law “opposites attract, likes repel” controls all magnetic interactions. This force makes magnets so useful.

When the North pole of one magnet comes near the South pole of another, their magnetic field lines link up. This pulls the magnets together. This is attraction.

When two like poles (such as two North poles) come near each other, their magnetic field lines push away from each other. This creates a repulsive force.

Think of it like puzzle pieces. The North and South poles are designed to fit together. Two identical poles are like trying to force two matching ends of a puzzle together—they simply won’t connect.

This basic force of attraction and repulsion is used in countless applications. From simple refrigerator magnets to complex high-speed motors.

The Inseparable Dipole

A common question is, “Can I have just a North pole?” Based on all experimental evidence, the answer is no.

Magnetic poles always come in a North-South pair. This pairing is known as a magnetic dipole.

The term “dipole” simply means “two poles.” It reflects the fact that magnetism, as we observe it, is basically a two-poled phenomenon.

Scientists have long theorized about the existence of a magnetic monopole—an isolated North or South pole. Such a particle is predicted by some advanced theories in physics. Its discovery would revolutionize our understanding of the universe.

However, despite extensive searches at particle accelerators like CERN, a magnetic monopole has never been found. For all practical and engineering purposes, every magnet is a dipole.

Earth's Giant Magnet

Our planet is itself a gigantic magnet. Its magnetic field extends thousands of kilometers into space. It forms the magnetosphere that protects us from harmful solar radiation.

Understanding Earth’s magnetic poles is crucial. It provides the context for navigation and clears up a common point of confusion.

Geographic vs. Magnetic Poles

Here lies a classic “aha!” moment in physics. The point on the globe we call the “Geographic North Pole” is the northern axis of our planet’s rotation. It’s a fixed point.

A compass needle’s North pole points toward a location near the Geographic North Pole. This location is called the “Magnetic North Pole.”

But remember the basic law: opposites attract. For a compass’s North pole to be attracted to the “Magnetic North Pole,” that pole must actually be a magnetic South pole.

This reversal is a critical concept. The pole we call Magnetic North for navigation purposes is actually the South pole of Earth’s giant magnetic field.

The table below clarifies these distinctions.

Term | Also Known As | What It Is | Where It Is (Approx.) |

Geographic North Pole | True North | The northern axis of Earth’s rotation. | 90° N Latitude. |

Magnetic North Pole | North Dip Pole | The point where Earth’s magnetic field points vertically downward. | Drifting, currently in the Arctic Ocean. |

Physics Truth | N/A | The “Magnetic North Pole” that a compass seeks is a magnetic South pole. | N/A |

Understanding Declination

The Geographic North Pole and the Magnetic North Pole are not in the same location. Furthermore, the Magnetic North Pole is not stationary. It wanders over time.

The angle between the direction to True North (geographic) and Magnetic North (the direction your compass points) is called magnetic declination.

This angle varies depending on where you are on the planet. For casual use, the difference is often small enough to ignore.

However, for precise navigation—such as for pilots, sailors, and serious hikers—accounting for declination is absolutely critical. Without it, you could be led off course.

Government agencies continuously track Earth’s shifting magnetic field to update navigation models.

A Practical Guide to Poles

Whether you are an engineer designing a sensor assembly, a student conducting an experiment, or a hobbyist working on a project, you will need to identify a magnet’s poles.

As experts who handle magnets daily, we use several reliable methods. These techniques range from classic scientific principles to modern technological shortcuts.

Method 1: The Compass

This is the most traditional and reliable method. It uses the known properties of Earth’s magnetic field.

First, lay your unmarked magnet on a flat, non-metallic surface. Any nearby steel or iron can interfere with the reading.

Bring a simple magnetic compass close to one end of the magnet. Don’t let it touch. A strong magnet can sometimes reverse the polarity of the compass needle.

Observe the compass needle. The end of the needle that normally points to Earth’s geographic North (the “North-seeking” end) will be attracted to the magnet’s South pole.

The end of the needle that normally points South will be attracted to the magnet’s North pole. This is a direct application of the “opposites attract” rule.

Method 2: A Marked Magnet

If you have a magnet with its poles already marked, this is often the fastest and easiest way to identify the poles of an unmarked magnet.

You simply use the law of attraction and repulsion. Bring the North pole of your marked magnet toward one end of the unknown magnet.

If the two magnets repel each other, you know that the end of your test magnet is also a North pole. Like poles repel.

If the two magnets attract each other, that end of your test magnet is a South pole. Opposite poles attract.

For this method to be reliable, you need a quality reference magnet. Using one of our high-strength NdFeB Magnets with clear markings ensures an accurate and clear test.

Method 3: Smartphone Apps

The modern approach uses a sensor that is already in your pocket. Most smartphones contain a magnetometer. This is the same sensor that powers their compass app.

You can download a dedicated “pole detector” or “magnetometer” app from your phone’s app store. These apps are specifically designed to read the polarity of a magnetic field.

Open the app and slowly bring your phone near the magnet. The phone’s sensor is usually located near the top edge.

The app’s interface will typically display “N” or “S” and a field strength reading. This gives you an instant identification of the pole. This method is fast, convenient, and surprisingly accurate for most applications.

Method 4: The DIY Compass

For a fun and educational experiment, you can create a makeshift compass to identify a magnet’s poles.

First, magnetize a steel sewing needle. Stroke it in one direction with one pole of a strong magnet.

Next, carefully place the magnetized needle on a small, floating object. A piece of cork or a small slice of foam works well.

Float this assembly in a bowl of still water. Keep it away from any other magnets or large metal objects.

Slowly, the needle will align itself with Earth’s magnetic field. The end that points toward geographic North is the needle’s North pole. You can now use this makeshift compass to test other magnets, just as you would with a real compass.

The Unbreakable Bond

What happens when you cut a bar magnet in half? Do you get a separate North pole and a separate South pole?

This is a classic thought experiment in physics. The answer reveals a deep truth about the nature of magnetism.

The Thought Experiment

The answer is definitely no. You cannot isolate a single magnetic pole by breaking a magnet.

When you cut a bar magnet in half, you do not get one piece that is all North and one piece that is all South.

Instead, you get two new, smaller magnets. Each of these new magnets immediately forms its own complete North-South pole pair.

If you cut those pieces in half again, you would get four smaller magnets. This continues down to the atomic level.

The Science of Domains

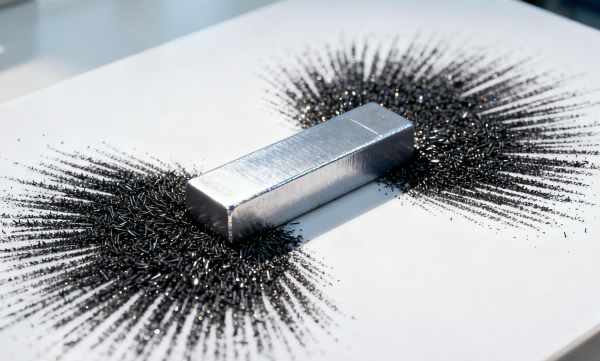

To understand why this happens, we must look inside the material. A magnetic material like iron or neodymium is made of countless microscopic regions called magnetic domains.

Each individual magnetic domain acts like a tiny magnet. It has its own small North and South pole.

In an unmagnetized piece of iron, these domains are all oriented randomly. Their tiny magnetic fields point in every direction, canceling each other out on a large scale. The material has no net magnetic field.

When the material is magnetized, an external magnetic field is used to align these domains. They all pivot to point in the same general direction. Their individual magnetic fields now add up. This creates a strong, large-scale magnetic field with a clear North and South pole.

Creating Two New Magnets

When you cut a magnet, you are simply splitting this large, aligned group of magnetic domains.

The new face you create at the cut instantly becomes a new pole. One side of the cut will have the “North” ends of all the tiny domains exposed. This creates a new North pole. The other side of the cut will have the “South” ends exposed, creating a new South pole.

The result is two complete, smaller magnets. Each has its own North and South poles. This basic principle is critical in manufacturing. When we create Custom Magnets, we are not just cutting material. We are engineering the final shape to ensure the aligned magnetic domains produce the exact field and pole configuration required for the application.

Poles in Real-World Action

Understanding magnetic poles is not just an academic exercise. For engineers, designers, and technicians, pole orientation is a critical design parameter. It determines the success or failure of a component.

The precise arrangement of North and South poles is what makes modern technology possible.

Engineering and Design

In product design, the direction of magnetic force is just as important as its strength. Pole configuration is key.

- Holding and Clamping: In a magnetic chuck or a holding assembly, the arrangement of alternating N and S poles is designed to focus the magnetic field lines. This creates a powerful clamping force on a workpiece. Incorrect orientation can weaken the assembly catastrophically.

- Sensors: Hall effect sensors are everywhere in automotive and industrial machinery for position sensing. They are activated by a specific pole. The sensor might trigger when a South pole passes over it but not a North pole. The entire system relies on this N-S distinction.

- Electric Motors: The rotation in an electric motor is a direct result of the rapid, controlled interaction between the magnetic poles of the rotor and the stator. The precise arrangement of alternating poles is engineered to create continuous attraction and repulsion, generating torque. The design of high-performance Motor Magnets relies on a perfect understanding of pole configuration to maximize torque and efficiency.

Medical Technology

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) machines are one of the most powerful applications of magnetism in medicine.

These machines use incredibly powerful superconducting electromagnets. They generate a magnetic field that is tens of thousands of times stronger than Earth’s.

The primary goal is to create a magnetic field that is not only immensely strong but also exceptionally uniform across the imaging area. This requires sophisticated control of the magnetic forces. It aligns the patient’s atomic nuclei to create detailed images of soft tissues.

The precise engineering of the magnetic field, governed by the principles of magnetic poles, is what allows for this non-invasive diagnostic miracle.

Data Storage

For decades, our digital world was stored on magnetic platters. Traditional hard disk drives (HDDs) used the principle of magnetic poles to represent data.

The surface of a hard drive platter is coated with a magnetic material. It’s divided into billions of tiny regions, or bits.

A read/write head, which is a tiny electromagnet, flies over this surface. To write data, it magnetizes a region with its pole pointing in one direction (such as North up) to represent a “1.” Or in the opposite direction (South up) to represent a “0”.

The ability to precisely control and read the orientation of these miniature magnetic poles was the foundation of digital data storage for generations.

Beyond the Bar Magnet

While the bar magnet is a great teaching tool, real-world applications use magnets in a variety of shapes and pole configurations.

Understanding these configurations is essential for anyone purchasing or designing with modern magnets.

Axial vs. Diametrical

For disc, cylinder, and ring magnets, two common magnetization patterns dominate.

Axial magnetization is the most common. The poles are located on the two large, flat faces of the magnet. If you were to stack these magnets, they would either snap together or push apart.

Diametrical magnetization is different. The poles are located on the curved sides, at opposite ends of a diameter. If you place this magnet on a flat surface, it will roll to align its poles sideways. This configuration is often used in sensors and motors where a side-on magnetic field is required.

Advanced Configurations

Engineers can arrange multiple magnets into complex assemblies. This shapes the magnetic field in unique ways.

One of the most powerful examples is the Halbach array. This is a special arrangement of individual magnets where the pole orientation of each magnet is rotated by a set angle relative to its neighbor.

This clever configuration has a remarkable effect. It strengthens the magnetic field on one side of the array while nearly canceling it out on the opposite side.

Halbach arrays are used in high-tech applications requiring a strong, one-sided magnetic field. These include particle accelerators, maglev train systems, and high-efficiency brushless motors.

The Power of Poles

From the simple definition of what are magnetic poles to their cosmic scale in our planet, their unbreakable nature at the atomic level, and their critical role in our most advanced technology, the journey of understanding is complete.

The simple duality of North and South is a fundamental force of nature. It is this opposition, this constant push and pull, that powers so much of our modern world.

We have seen that magnetic poles are not just points on a magnet. They are the gateways to a powerful, invisible force.

Understanding them is the absolute key to unlocking the full potential of magnetism. Whether for a simple DIY project or a complex engineering marvel.

We are a manufacturer specializing in the research and development of magnets with years of industry experience. Our product offerings include NdFeB magnets, ferrite magnets, and custom magnetic components. Our goal is to provide high-quality magnetic solutions to customers worldwide, and we also offer OEM/ODM customization services. If you have any questions about magnets or custom applications, please feel free to contact our team of experts.

Facebook

Twitter

LinkedIn

WhatsApp